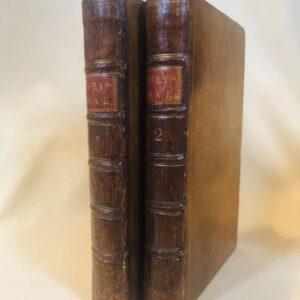

Limited to 11 copies in full black leather

and 170 copies in red quarter leather and black linen

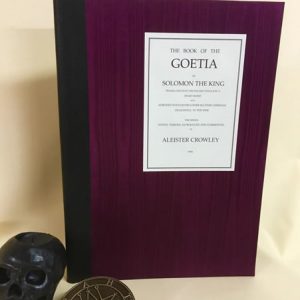

This work contains Matthew Hopkin’s treatise on witchcraft from 1647 and an essay about Hopkins by Montague Summers. Hopkins was England’s self-proclaimed Witchfinder General. From 1644 until 1647, he travelled from village to village, trying and torturing those unfortunates accused of witchcraft. England was going through a civil war, and the state of political turmoil made it possible for Hopkins to assume authority and roam about as he pleased, burning witches and torturing as he went. It is believed that he was responsible for the deaths of 300 people. (This equates to more than half of the total number of witches killed in England from 1400-1700.) The legend is that he stole the Devil’s list of names from Lucifer himself, and that’s how he knew where to look and who to interrogate.

Hopkins’ pamphlet takes the form of a dialogue between himself and a person who is not convinced of the legitimacy of his activities. He explains how he began his witch hunt, the nature of witchcraft and the different methods of ‘examining’ a witch. These different forms of examination were really just different varieties of hideously sadistic torture. Hopkins was a notorious witch-pricker. He and his accomplices, John Stearne and Goody Phillips, would spend hours sticking needles into innocent women’s flesh. If they found a spot that would not bleed, this was taken as proof of diabolic interference. (The Devil always left his mark somewhere on his servants’ bodies, and the spot where he left this mark would not shed blood.) In Hopkins method though, pricking was only a preliminary method of testing. If the results weren’t conclusive, the witch would be ducked.

Other suspected witches were either ‘watched’ or ‘walked’. Watching a witch involved placing the crone in a room with a small chink or hole in the door until she either made a confession or something else occurred to prove her guilt. She would be forced to sit in an awkward and painful position, and tied up if she refused to remain still. The watchers would keep an eye out for spiders or small flies that slipped into the room through the fissure in the door. If they were unable to squash these bugs, this would be taken as proof that they were actually the accused’s familiar spirits come to relieve their master in her hour of suffering. An elusive midge could provide interrogators with enough evidence to send a witch to the gallows tree. Watching sessions could last days, and the witches were starved throughout.

‘Walking’ was when witches were deprived of sleep and energy by being forced to stay up all night, running back and forth in a small room.

Hopkins also provides an entertaining list of the names of all the witches’ familiars that he encountered. He claims that these wicked spirits have “names which no mortall could invent”, and while Ilemauzar, Pyewackett, Jarmara, Jeso, Holt, Saoke, Griezzel, Wynoe, Panu, and Mrit are all quite unusual sounding, Pecke in the Crowne, Vinegar-Tom, Jockey, Sugar, Newes, Littleman, Prettyman, Dainty, and Greedigut all sound very much like they were invented by a mortal, and that’s not to mention the familiars Elizabeth, Collyn and Sandy.

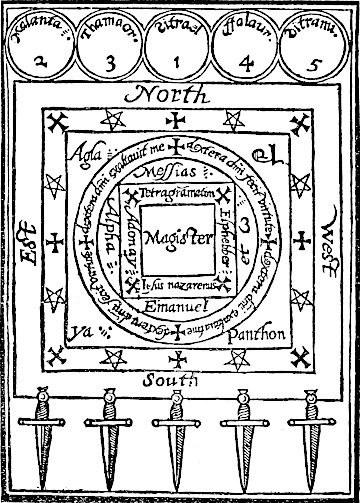

Added to the end of this publication is a short article by Gerald B. Gardner, founder of modern witchcraft, relating the details and images of items said to have been used and kept by Matthew Hopkins himself.